Thanks to a grant from the Biodiversity Foundation, researchers from the Forest Science and Technology Centre of Catalonia (CTFC), Sarga technicians (Government of Aragon), researchers from SECEMU (Spanish Association for the Conservation and Study of Bats), researchers from the CSIC of Doñana, from the Leibniz Institute in Berlin and specialists from the Groupe Chiroptères de la Société Française pour l’Etude et la Protection des Mammifères have studied the population and movements of the Greater Noctule bat (Nyctalus lasiopterus) in the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula using isotopes. In turn, several teams of scientists over the years have ringed and chipped several specimens in order to obtain recapture data and try to better understand the disparate annual movements that this species seems to make in the biogeographic zone of southwestern Europe.

Un individuo de nóctulo gigante de la Fageda d’en Jordà (Parque Natural de la Zona Volcánica de la Garrotxa). Autora: Laura Torrent.

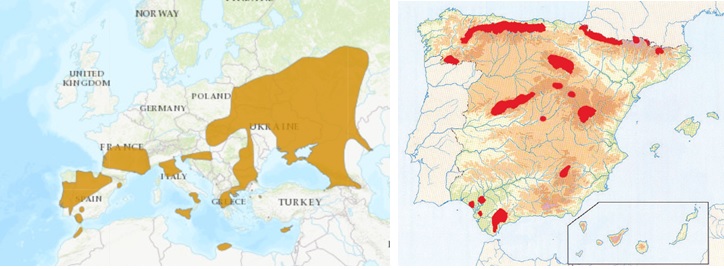

The Greater Noctule is the largest bat in Europe, it has a wingspan of between 410 and 460 mm and can weigh up to 60 grams. Its size allows it to feed not only on insects but also on small birds, unlike other European bats, which are basically insectivores. It is a threatened species, of priority conservation at European level, according to the Habitats Directive, and considered as Vulnerable in the Spanish Catalog of Threatened Species.

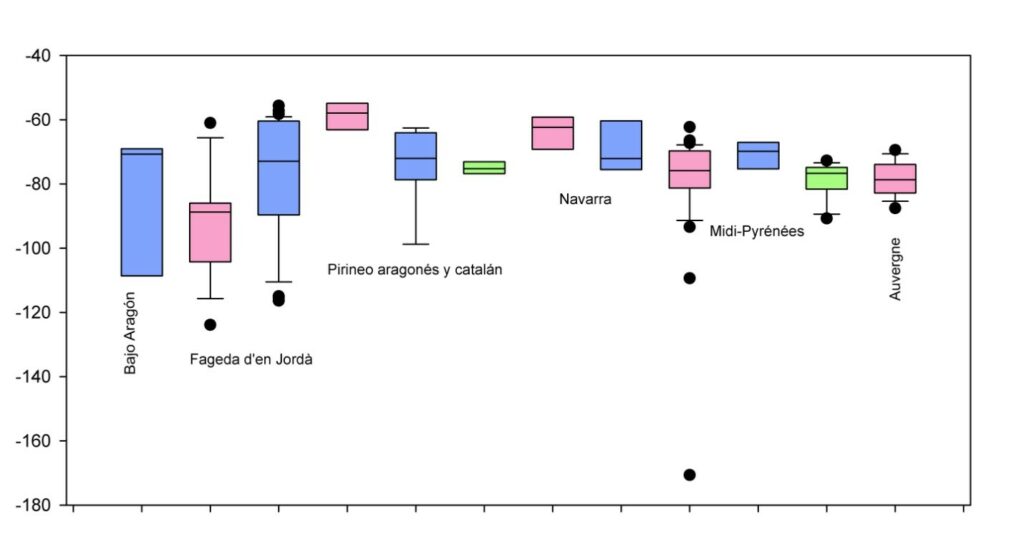

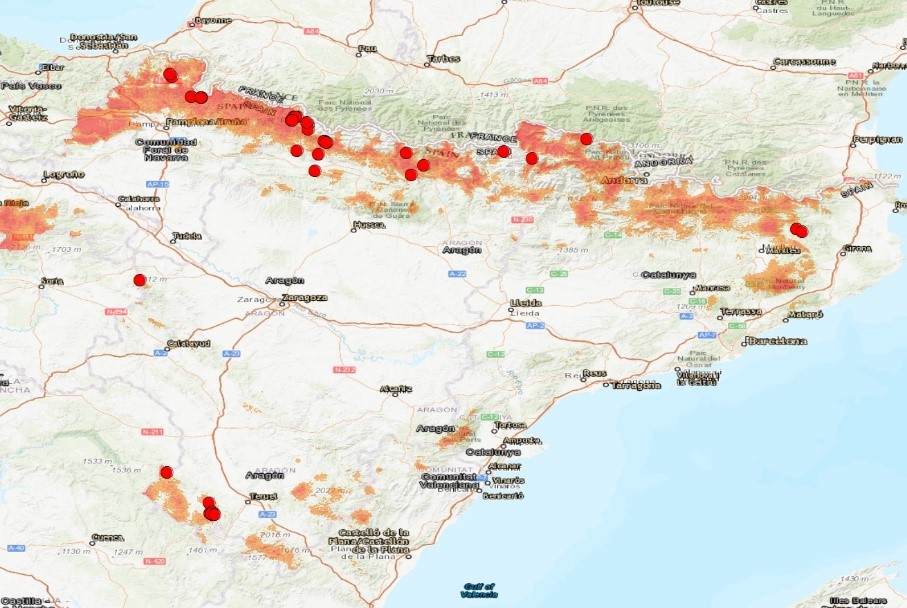

Based on the study of the isotopes, it seems that the populations of the north of the Iberian Peninsula are partially migratory. Specifically, the populations of males and females in Navarra seem to be either quite sedentary or they would make a regional migration of a few kilometers. On the other hand, some males from the Aragonese Pyrenees would make a regional migration (according to the isotope data), from the mountain areas of the Pyrenees to more southern areas of Aragon (e.g. Teruel) or to populations in southern France (Figure 1). On the other hand, it is seen that there is a great diversity of isotopes in the females of the center of France and not so much in those of more to the north (Dep. De Auvegne). It seems that these females would be the ones that could travel greater distances towards southern areas, as the recapture of the marked female in Catalonia has been demonstrated. Lastly, the male populations of the northeast of Catalonia are sedentary and it is the females that seem to migrate from the center or the north of France (figure 1). In fact, it is the only group significantly different from the others in terms of its d2H values with respect to males from the same locality (median -88.74 ‰ versus -72.92 ‰, U = 153, P = 0.009).

Figure 1. Box plots of the 2H (‰) values of Greater Noctules by regions and sex and age groups. Blue: males, Pink: females, Green: juveniles. Source: Ana Popa-Lisseanu (FB 2017).

Thanks to the recapture of a Greater Noctule female that was found breeding in May 2019 in Vezin-de-Lévézou (Parc Regional de Causses, France) and that was ringed for the first time by CTFC researchers on November 30th, 2016 in la Fageda d’en Jordà (La Garrotxa Volcanic Zone Natural Park, Catalonia) confirms for the first time the hypotheses raised by isotopes studies. The Greater Noctule female had made a 236 km straight migration from the matting and wintering site to the breeding area. It should be noted that it is the first recapture of this species in another country.

All of this opens a door for us to establish more lineages between the Pyrenees and southern areas of the Iberian Peninsula and for this reason it is important to ring Greater Noctule females in all areas.

Distribution of the Greater Noctule bat in Europe, in orange, and in Spain, in red. Source: IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and Guixé et al., 2018.

Potential distribution, in orange, and known population points, in red, of the Greater Noctule bay at the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula. Source: Guixé et al., 2018.

The main problem of the Greater Noctule is the lack of mature forest stands, especially deciduous or mixed forests with an abundance of natural cavities and woodpecker holes where they place their daytime roosts. For this reason, it is crucial to protect existing mature forests and, in forests managed for timber production, to preserve clumps of large, old, decayed or standing dead trees, which provide natural roosts for bats.

It is also important to promote free-evolving forest stands, so that the maturity stages can advance. This can be achieved, for example, by declaring forest reserves in public forests or by establishing agreements with private farm owners. These actions are a priority wherever the species has been detected.

Bats are the most unknown group of mammals in Europe, but also the second most diverse after rodents, of which all species are protected and many of them threatened. All European bats are insectivores and key species in the ecosystems. They are an important ally of agriculture and forestry as controllers of insect pests. These facts justify the importance of working to know and improve their populations and ensure their conservation.

The work team has been made up of David Guixé, Jordi Camprodon, Laura Torrent, Elena Roca, Xavier Florensa, Ramon Jato, Luís Lorente, Juan Tomás Alcalde, Ana Popa-Lisseanu, Lionel Gaches, Yannick Beucher and Marie-Jo Duborg. We are grateful for the help of the technicians of the La Garrotxa Volcanic Zone Natural Park and the Fauna and Flora Service of the Department of Territory and Sustainability of the Generalitat de Catalunya.